GOD NTR

THE KISWAHILI-BANTU RESEARCH UNIT

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN LANGUAGE

The De-agglutination and Agglutination of the Emblem of Divinity NTJR, NTR.

![]()

![]() NTJR-NTR:

The Emblem of Divinity

NTJR-NTR

NTJR-NTR:

The Emblem of Divinity

NTJR-NTR

![]()

Researched by Ferg Somo

There has

been much thought provoking attempts by scholars throughout the ages to try

and understand the significance and meaning behind the Ancient Egyptian emblem

of divinity seen here ![]() pictorially.

pictorially.

The Ancient Egyptians left us without any clues about their sacred emblem. Sir Alan Gardiner in his book on Ancient Egyptian grammar thought that the emblem was a ceremonial flag. However on closer examination and by researching the subject in depth I have found that the emblem of divinity does not represent a ceremonial flag.

In this exploration, the linguistic aspects of the Kiswahili-Bantu language will be used together with other Bantu languages to heighten support in establishing the Ancient Egyptian word for God. I shall derive important meanings from the Ancient Egyptian word by using the Kiswahili-Bantu language and linking it to the familiar phrase 'Mdw Ntr', the words spoken by God, in short the term used for hieroglyphics or divine speech. The evidence I provide have been found to be true especially when the word for God in Ancient Egyptian is compared with the word for God as The Creator or the designer of all in a particular Bantu language. The particular Bantu language which uses the identical word for God as The Creator will be discussed later once an in-depth exploration has been made. We have been able to overcome the difficult task of unlocking the common etymology of the word. Finding the correct etymology has up to now evaded analysis by modern scholarship. I hope this important discovery will further raise awareness of the important research being carried out on the linguistic structure of the Ancient Egyptian language and the indelible evidence presented here will stand the test of time. The etymology of the word discovered will not falter. It will endure and overcome critical analysis by members of the public. This is not a study in religious education. It is a study substantiated with real evidence derived from common observations made between the Kiswahili-Bantu and Ancient Egyptian language. The word we have researched is the actual word the Ancient Egyptians would have used for their God.

The ideas which represent the Ancient Egyptian emblem of divinity are firmly based on ancient Bantu traditions. The consonants which make up the image of the emblem of divinity are many and, present one with different pronunciations of the word. According to Sir Alan Gardiner, when the emblem of divinity is given on its own, it is to be read as NTJR. However when a female deity is represented the consonants change to NTR. The TJ sound representing male deities changes to the T sound when representing female deities. One would not expect to see such changes in sounds. Generally speaking the Ancient Egyptians used an identical stem to denote a masculine or feminine noun, but would use a different ending for the feminine case. The letter T, at the end of the stem of the word was used to signify a feminine noun. However there are always exceptions to the rule.

Scholars of the Ancient Egyptian language have tried to look for the correct etymology of the Ancient Egyptian word for God in the Coptic language. However the Coptic word for God is NOUTE. Like most words which describe God, the etymology of the Coptic word for God has never been analyzed. In other words the root of the word is unknown. The Coptic word for God NOUTE does not inform us who God is or what is the function of God. This poses an even greater enigma for such a fundamental word which should have retained its radical root and remained stable over the centuries since Coptic and Ancient Egyptian are said to be closely related languages.

In trying to establish a meaning to, who God is or what God does, scholars of the Ancient Egyptian language have described the emblem of divinity in the following ways: mighty, might, strength, power, powerful, or power to renew. Whilst there may be some truth in these descriptions, they must remain speculative since the etymology and precise meaning of the word representing the emblem of divinity is not known at this stage. We have established through research that the Ancient Egyptian term for God is closely related to the Bantu model describing God as a creator or maker. First and foremost, the Bantu model sees God as being the creator who shapes and forms like a potter.

From linguistic observations, we have established that the Ancient Egyptian word for God, defined by the consonants, NTJR, or NTR, contains a verb which is hidden within the consonants. Identifying and unlocking the hidden verb has taken five years of trial and error study.

![]()

THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN EMBLEM OF DIVINITY

THE ETYMOLOGY OF NTJR, NTR

The Ancient Egyptian emblem of divinity must be seen in terms of Bantu cultural traditions. Might and power are essential qualities for a nation to survive. Thus the emblem of a spear or a hand axe signifies authority to rule and govern. Some Bantu cultural traditions have abandoned the hand axe as an emblem of authority, but have retained the spear. In Luvale-Bantu traditions a hand axe called CHI-MBUYA, was carried by a male chief as an emblem of authority.

The image of the Ancient Egyptian emblem of divinity is similar to the hand axe or spear in Bantu tradition and denotes supreme power and authority. Thus the Ancient Egyptian God was associated with the symbol of the cutting edge of a hand axe. A spear with a point and a flat cutting edge is commonly seen in Southern Africa as 'The Spear Of The Nation', for it propels a forward lead giving direction by its piercing point. The stopping force of a spear is a measure of power, the authority to rule and govern.

Thus the emblem of a weapon is used as an image associated with power and authority. The Ancient Egyptian emblem of divinity represented the power of God and the emblem portraying this was nothing more than the hand axe. Confusing this with a ceremonial flag as Sir Alan Gardiner did does not stand up to the evidence. So how may one confirm that a hand axe was used by the Ancient Egyptians to signify the divine nature of their God?

Consider:

POINTEDNESS AND SHARPNESS

Having a point on a weapon such as a spear or having the sharpness of an axe is commonly associated with power. Hence in Southern Africa it is frequently acknowledged in casual conversation, that:

'A person who possesses a pointed tool is capable of undertaking anything'

Such a person is described as NCHORI, a point, a pointed tool.

So how can one confirm with absolute certainty that the ideas examined were

adopted by the Ancient Egyptians? What clear evidence do we have to back up

the research?

Fortunately we are able to draw on the linguistic evidence embedded within

the consonants NTJR, NTR.

However before we get to the evidence

let us consider a few concepts relevant to our study.

Consider the concepts of:

ARRANGEMENTS AND ORDERLINESS

'MAKING REGULAR'

'Arrangement' and 'Orderliness' are the key underlying ideas embedded within the consonants NTJR, NTR. The idea of 'making regular' means to achieve an orderly state by systematic arrangements, a state of total equilibrium or harmony. Making regular is to conform to normal principles, to make correct, proper, to be well ordered, to fit. Thus the creation of the universe is commonly seen as being 'regular' or 'orderly'

The conditions giving rise to orderliness is

generally attributed to the creative power of a supreme being we call God.

Concepts of symmetry, harmony, are likewise states of orderly arrangements.

'Making regular' by ordering, arranging, making equal, are conceptual

ideas found within Bantu and Kiswahili-Bantu words. Bantu languages are seen

to be orderly, for they classify and arrange words in a well

ordered-structured way. The Ancient Egyptians too shared these concepts and

used them to define their emblem of divinity.

HOW WAS THIS DONE?

To understand these conceptual ideas, consider the Kiswahili-Bantu word 'ANDAA'.

The fundamental meaning is, to prepare, or to put in order. 'ANDIKA',

which is derived from the same stem as ANDAA, means, to put or lay on,

to apply anything to, to besmear, to plaster, to set in order, lay out and

arrange, write, (make a mark), enroll, register in a book.

It is becoming clear that,

'Writing is the laying down of orderly arrangements'

It conforms to systematic sets of principles. These principles are traditions vividly expressed in Bantu geometric art and network designs. Thus writing, painting or incisions made on the body are commonly considered to be states of orderliness. These states of orderliness are harmonizing arrangements of artistic forms, brought about by oral ancestral beliefs, usually divine in nature and passed down through the generations.

Consider next:

THE ETYMOLOGY

OF THE KISWAHILI-BANTU WORD CH-ORA, J-ORA, T-ORA

The Kiswahili word CH-ORA, J-ORA, T-ORA, with its many pronunciations, is an interesting word with an etymology derived from the common Bantu verb form -ORA or -OLA. The basic understanding of the verb has the underlying idea of 'making regular'. As an example consider pouring water from one pot to another to fit the quantity for a meal. The action in this instance is seen as 'making regular' and denotes a final state of completion, equilibrium, balance and orderliness. The ideas above carry forward to the following meanings of the verb -ORA, or -OLA, to trace, engrave, mark and carve a design. These descriptions of the verb -ORA, -OLA conform to 'making regular'. The actions are seen as orderly arrangements, laid down and established by a set of traditionally accepted rules. They also form the basis of Bantu initiation and ceremonial practices. Markings or writings are therefore religious acts, and are sacred. They help to establish cultural identity and are seen as spiritual anchors of ancestral beliefs.

Meanings of the Kiswahili-Bantu word CHORA in Bantu languages

The word CH-ORA is also pronounced as J-ORA or even T-ORA in the Kiswahili-Bantu language. The prefixes, CH, J, or T are interchangeable. Several types of prefixes of the verb may be used, and vary between Bantu languages. Here are a few examples with a wide range of meanings derived from the verb -ORA, or OLA. Notice the various types of Bantu prefixes used.

Southern Sotho-Bantu

NG-OLA means to engrave, to draw, to write, to register.

MA-NG-OLO (noun, plural form), The Bible, the Holy- Scriptures

Shona-Bantu

NY-ORA, Tattoo marks (noun form) Make marks with soapstone, write

NY-ORWA (noun form) Writing, Scripture

MU-NY-ORI Writer, Secretary, Editor

Kiswahili-Bantu

T-ORA, CH-ORA, J-ORA, (verb) to carve, to adorn with carving, make

ceremonial incisions to the body, engrave with a pointed tool, write, draw,

design, paint

T-ORA, (Noun form) small spear,

T-ORA, orderliness,

T-ORA, (Verb) cackle.

T-ORO, CH-ORO means that which is carved or written, carving, writing,

hieroglyphics and ethnic tattoo

Kinyika-Bantu

NS-ORA, means that which is carved or written, carving, writing.

'Ku-ora nsora', to write a letter

Luganda-Bantu

LUY-OLA, Cutting on body for ornament, ethnic mark.

NJ-OLA (plural form) Carvings, cuttings, thread of screw, 'Ethnic' marks.

The study set out so far must be seen in terms of establishing a common link

between Ancient Egyptian and Bantu religious initiation practices. The

question one poses is this; did the Ancient Egyptians use the same word,

TORA, CHORA or JORA?

Is it possible to establish a similar word in the Ancient Egyptian vocabulary?

If the word, CHORA, TORA or JORA did exist in the Ancient Egyptian language then clearly there must have been a common point of origin a common ancestry, between Bantu and Ancient Egyptian.

The etymology of the word, TORA, CHORA, JORA was known by Ancient Egyptians, and they used the word CHORA, TORA, JORA with different prefixes in similar ways as in Bantu.

Let us establish whether the Ancient Egyptians used the word TORA, CHORA or JORA. The findings must contain clear supporting evidence. Before we attempt to analyse the word any further, let us consider various hieroglyphics which help to establish different sounds in the Ancient Egyptian language. We shall compare them to the Kiswahili-Bantu language.

The Ancient Egyptian TJ sound

Budge 855a

TJMA![]()

The hieroglyphics TJMA means strong, courageous, brave and bold.

This is given as CHUMA or JUMA in Kiswahili-Bantu.

The hieroglyphics consists of a tethering rope followed by the sickle sign. The tethering rope presents us with a shifting sound value. Sir Alan Gardiner states [see Egyptian Grammar, Gardiner pg 27] that it was originally approximated to the following sounds, TSH or TJ. During the Middle Kingdom the sound persists in some words, while in others it is replaced by the T sound. The Kiswahili-Bantu language has the identical sound shifts and is in keeping with the Ancient Egyptian language.

Let us examine a few sound shifts in the Kiswahili language before analyzing the above hieroglyphics.

Examining sound shifts

The Kiswahili-Bantu word CH-ORA, J-ORA, T-ORA, and its equivalent

sounds in other Bantu languages may now be examined and compared with the

Ancient Egyptian sound given by the hieroglyphics above. Studying the shift in

sounds are important indicators, for they help to establish further linguistic

evidence. In Kiswahili and other Bantu languages, the sound shifts are largely

based on localised accents. These traits are universally inherent within all

languages.

Consider the following equivalent sounds:

In Kiswahili-Bantu CH-ORA as in CH-URCH, Ancient Egyptian TJ

sound

Kiswahili-Bantu T-ORA as in T-OWN, Ancient Egyptian T sound

Kiswahili-Bantu J-ORA as in J-OHN, Ancient Egyptian TJ sound

Kinyika-Bantu S-ORA as in S-UN, Ancient Egyptian TSH sound

Next consider different shifts in sounds for a word used in different regional areas where the Kiswahili-Bantu language is spoken. Consider the word, 'To pasture, to tend animals'. There are various ways of pronouncing this word, CH-UNGA, SH-UNGA, TU-UNGA. Hence the sound changes are CH, SH, T.

Consider again another word which is pronounced differently in Kiswahili-Bantu. The word for a book is CH-UO, TJ-UO or J-UO. The sound changes are, CH, TJ, J.

The Ancient Egyptian TJ sound is similar to the Kiswahili CH, or J, sound. We can test and compare the two sounds by examining the hieroglyphics.

Budge 855a

TJMA![]()

Ancient Egyptian: TJMA, brave, strong, bold

Analysing the hieroglyphics and using the sound given in the Ancient Egyptian letters TJMA, the transliteration in Kiswahili-Bantu is given by the word CHUMA, or JUMA.

Several meanings may be derived from the Kiswahili word CHUMA or JUMA. These are:

CHUMA iron, steel, weapons, arms, (or gold in Shona-Bantu)

CHUMA Strong, bold, courageous, brave, strong person, man of steel, a champion, a person with superhuman qualities, a hero, a supreme being.

The Kiswahili descriptions of the word CHUMA match the Ancient Egyptian meanings, word for word.

![]()

Budge 855a

TJMA, a God

It is no wonder that the Ancient Egyptians named one of their Gods CHUMA.

This makes him a hero, a supreme

being, a supreme ruler.

Now that we have established the Kiswahili-Bantu and Bantu sound values, CH, J, T, we can analyse the Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics shown below.

Budge 857a

![]()

The hieroglyphics TJRW, Painting, writing,

The hieroglyphics consists of the tethering rope and has the sound TJ. This is followed by the symbol of a mouth with sound value R, followed by the quail chick, and sound value R. The whole set of hieroglyphics ends with the scribe's outfit.

Kiswahili transliteration, CH-ORWA, T-ORWA means '(Something) written' or '(Something) painted', a painting, writing.

Compare this with the Kinyika language, NS-ORA- 'that which is carved or written', or to the Shona-Bantu language, NY-ORWA- 'Writing, Scripture'.

Thus the evidence is becoming clear. The Ancient Egyptians did use the Kiswahili-Bantu word, CHORA, TJORA, or TORA. Thus the etymology of the Kiswahili word CHORA, TJORA, or TORA was known to the Ancient Egyptians.

The Ancient Egyptians used the word TORA to describe the emblem of divinity and linked the word to their God.

The visual evidence

The AXE as the emblem of divinity

![]()

Remember the saying:

'A man with a pointed tool is capable of undertaking anything'

Further evidence to substantiate the fact that the emblem of divinity was a hand axe may be obtained from the sculpture shown above. The sculpture shows an unmistakable African-looking warrior accompanied by his mate. He is leaning forward in an attacking position and seen in full action, clutching a spear and shouldering a protective shield whilst holding the unmistakable form of a hand axe which appears to be not too dissimilar in form to a flag. The confusion between a flag and a hand axe is quite discernable in this instance. Thus the spear, shield, and hand axe were sufficient and necessary weapons of war in the year 1352 BC.

Quite simply the emblem of divinity represented an implement with a sharp cutting edge, similar in form to a carving or cutting tool, an instrument which carves- a CARVER, or an AXE. It is interesting to note that Ancient SAXONS used the SAXON AXE, as an anchor of SAXON power and identity.

BASOTO BATTLE AXE

BATTLE AXE, KASAI, Congo (D.R.) Axe with iron or steel blade with small circular perforations. Shaft covered with snake skin.

NYAME AKRUMA, GOD'S AXE

THE AKAN SYMBOL OF GOD

The AKAN symbol is based on Neolithic axe heads, found in the region, and considered by the Akan people to be the physical remains of thunderbolts hurled by angry Gods. The Akan would often wear one or more shells as a talisman against lightning strikes (and later as protection against firearms).

THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SYMBOLS OF GOD

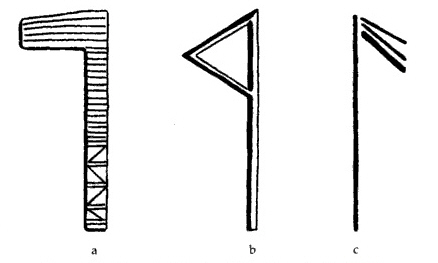

The three symbols seen below show the visual depictions of the Ancient Egyptian's symbols which portray God. The first symbol is a depiction of a staff bound with a cloth, thus expressing the concept of a flag as given by Sir Alan Gardiner. The third symbol is a flail, an agricultural implement which uses force just as an axe is used for carving or cutting.

In all the three symbols depicting the God as NTR, we observe that the symbols display some form of physical force, violence or strength which have became symbols of domination associated with NTR in predynastic Egypt. The ideas behind the axe as a symbol of divinity is not new, in fact many cultures around the world make use of it as may be seen above.

Now that we have established a visual representation of the hand axe to be a symbol of power, divinity, we can attack the subject linguistically.

The Linguistic Evidence of the AXE HEAD

ANALYSING NTJR

NTJR, NTR. THE SYMBOL OF DIVINITY, GOD

Dis-agglutinating NTJR= N +TJR

N + CHORA [TJORA, TORA]

[That which, He who] + [Cuts, writes, engraves hieroglyphics]

The consonant N is a Bantu prefix formative morpheme, interchangeable with the MU morpheme. It denotes 'something pertaining to' a term of reference, 'That which is or the one who is'. As an example the Kiswahili-Bantu word MTU means a person and can also be pronounced as NTU.

THE KISWAHILI-BANTU MEANINGS OF

N-CHORA, N-JORA, N-TORA

Agglutinating:

N + CH-ORA = NCHORA.

Consider

some meanings from the above verb form, CHORA, TJORA, TORA.

The Kiswahili-Bantu meanings for the noun form of the verb, N-CHORA,

N-JORA, N-TORA or (MU-CHORA) may be given by the following: That

which carves or cuts'. In other words a carving or cutting tool, i.e. a

carver.

Since the hieroglyphic denotes a picture of an axe, then the axe was called NCHORA, or NTORA, a carver, a carving tool, NCHORA = 'THAT WHICH CARVES'.

N-CHORA

The Designer

The Author of HIEROGLYPHICS-- the word

To design is to plan and arrange something artistically. Thus a designer is a

person who draws up original plans from which things are made.

N-CHORA (Refer to Shona-Bantu, MU-NYORI) a writer, an author, an engraver

An author is the beginner or the first mover of anything. Thus a writer, author or engraver of writing is considered to be an originator or creator. Recall the saying "God is the author of our being' The Ancient Egyptian emblem of divinity embraces the wide variety of meanings, which are derived from an implement which carves, a carver, an axe.

Thus N-CHORA is a person who

carves and paints HIEROGLYPHICS.

NCHORA is THE WRITER OF HIEROGLYPHICS.

NCHORA is THE TEACHER OF HIEROGLYPHICS.

The different sound shifts in the words have similar meanings and may be

interchanged without loss of meaning. Shifts in sounds occur when a change in

accent exists. Regional variations always affect shifts in sound patterns.

Thus N-CHORA, N-JORA, N-TORA is the symbol of an axe, a carving tool,

'that which carves'. It is also a symbol for 'The one who creates

hieroglyphics', a creator.

The Ancient Egyptians dedicated the emblem of an axe to God. It was God who had the power and ability to plan, design, carve and write down hieroglyphics. It was God who possessed the carving tool, the axe. It was God who had the ability to make final decisions. It was God who was the final claimant.

Finally the question which arises is this: Did a particular Bantu language use the same ideas we have studied above linking the verb CHORA or TORA to give the words NTORA, NJORA or NCHORA, a word which describes God in the Ancient Egyptian language?

THE SYMBOL OF DIVINITY

![]() GOD

GOD

![]()

[Kuria-Bantu] GOD = KENG'-OORI = GOD [Kuria-Bantu]

Kiswahili-Bantu = NT'ORA, NT'ORAI, NT'ORI = Kiswahili-Bantu

NCHORA - NTJR = ANCIENT EGYPTIAN = NTR - NTORA

GOD, THE CREATOR, DESIGNER OF ALL

After many years of researching the word for God it has been possible to identify a Bantu language which uses the verb -OORA as a root in its construction for deriving the word used for God. By analyzing the Eastern Bantu language known as KURIA-Bantu spoken widely around the Nyanza province we are able to obtain resemblances to the following words analyzed before.

In the Kuria-Bantu language -NG'-OORA, means to design or draw a pattern, fashion, create, characterize. Again compare this to CH'ORA or T'ORA in the Kiswahili-Bantu language. These definitions in meanings when compared to the words of other Bantu languages suggest a commonality of root. By using various prefixes and the stem of the verb one is able to obtain the following forms;

ENG'-OORO, a pattern, a design, luck, character, destiny, how a person is made

EKENG'-OORO or EKENG'-OORAI, a design, pattern, how one's made, destiny

Finally we arrive at the word we are looking for:

The Kuria-Bantu pre-Christian word KENG'OORA or KENG'-OORI is the word for God-'The Creator' 'The Designer of All'. The equivalent word in the Kiswahili-Bantu language is NT'ORA 'The Designer'

Thus NTJR or NTR have the following

meanings:

- He was THE CREATOR (Kuria-Bantu KENG'OORA

· He was the one who established order, NTORA.

· He was the possessor of hieroglyphics, NCHORA.

· He was the author, NCHORA.

· He was the one who arranged orderliness, NTORA.

· He was the carving tool, NCHORA.

· He was a teacher, NCHORA.

· He was NCHORA.

· He was NTJORA.

· He was NTORA.

· He made 'ethnic' incisions in the body, NTORA.

· He came from Ancient Africa, NTORA

· He came from Ancient Egypt, NTJORA.

· HE was?... NCHORA...

· HE was?... NTORA.

· HE was?... NTJORA . NCHORA=NTJORA=NTORA

HE WAS 'THE GOD OF ANCIENT EGYPT'

.... NCHORA, NTJORA, NTORA....

Copyright © 13 June 1999, Ferg S. All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (via the Internet or any World Wide Web Site or electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, by recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Email: Ferg@kaa-umati.co.uk

Website: www.kaa-umati.co.uk

References:

Carruthers, J. (1995). MDW NTR: Divine speech, a historical reflection of African deep thought from the time of the pharaohs to the present. London: Karnak House.

Obenga, T. (1992). Ancient Egypt and black Africa: A student's handbook for the study of ancient Egypt in philosophy linguistics and gender relations. Chicago: U.S. Office and Distributors: Front Line International (751 East 75th Street, Chicago, IL 60619).